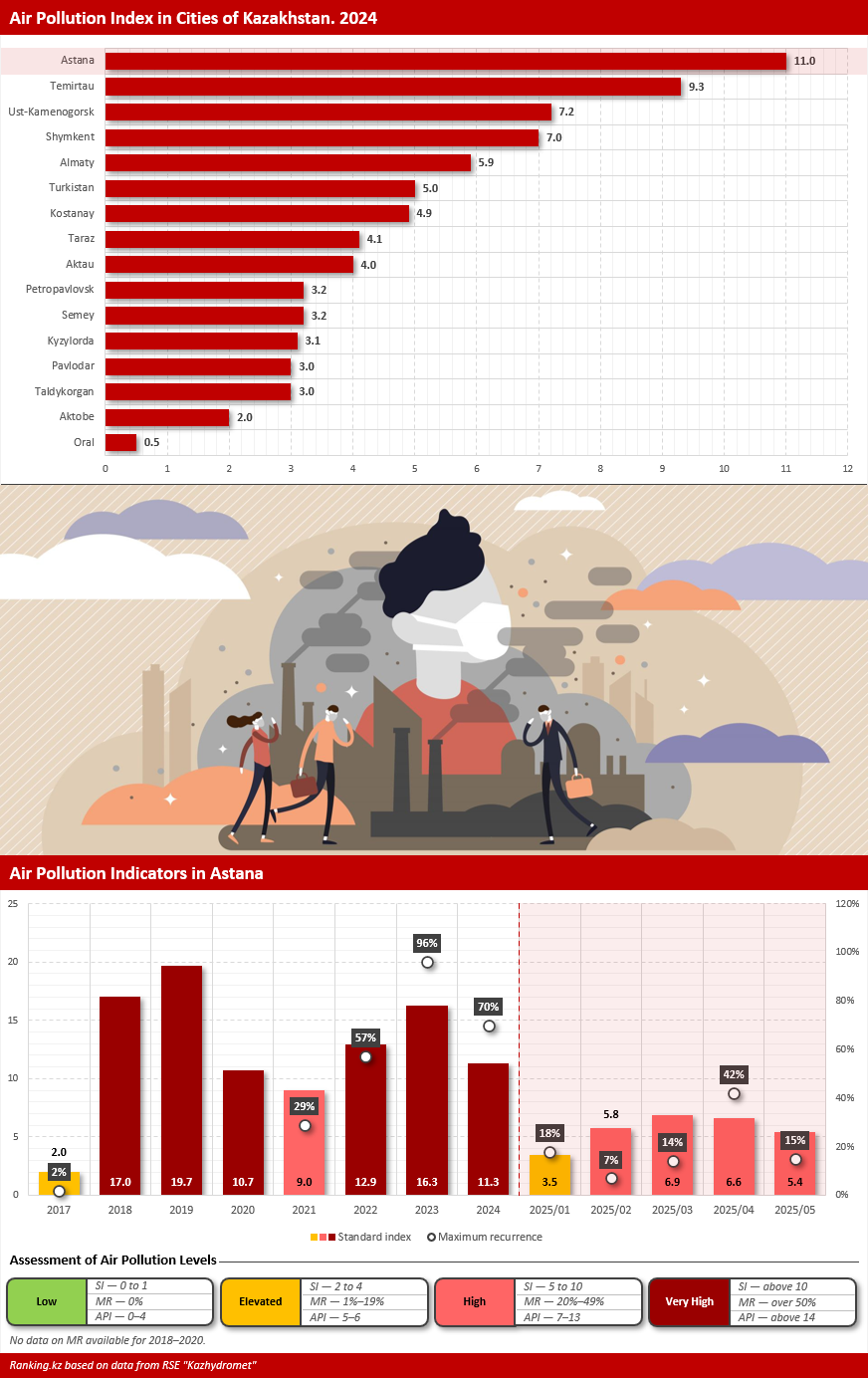

Kazhydromet experts have listed Astana as the top city with consistently high levels of air pollution between 2021 and 2025. Alongside the capital, other cities in this category include Almaty, Karaganda, Aktobe, Temirtau, Satpayev, Petropavlovsk and Talgar. The main benchmark for evaluation was the annual Air Pollution Index (API). Last year, Astana topped the list, recording an API of 11 — the highest in the country.

The primary pollutants in Astana’s air are hydrogen sulfide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, ozone and particulate matter. In 2024, the average daily maximum allowable concentration (MAC) for ozone was exceeded by a factor of 3.2, and by 1.8 times for fine dust particles. The highest single-time concentrations were significantly more severe: hydrogen sulfide reached 11.3 times the MAC, ozone — 7 times, PM2.5 particles — 6.7 times, nitrogen dioxide — 4.9 times, sulfur dioxide — 4 times, nitrogen monoxide — 2.5 times, and carbon monoxide — 3.2 times. In total, environmental sensors recorded tens of thousands of such exceedances throughout the year.

Kazhydromet uses two key monthly indicators to assess pollution trends: the Standard Pollution Index (SPI) and the Highest Recurrence Rate (HRR). From January to May this year, the combination of these indicators pointed to elevated and high levels of air pollution.

Despite the fact that Astana does not face significant environmental barriers — unlike Ust-Kamenogorsk, where metallurgical plants operate within city limits—the capital is following the path of an ecologically overloaded metropolis. High levels of air pollution are observed not only in winter, when thermal power plants operate and private homes emit smoke, but also in spring and summer.

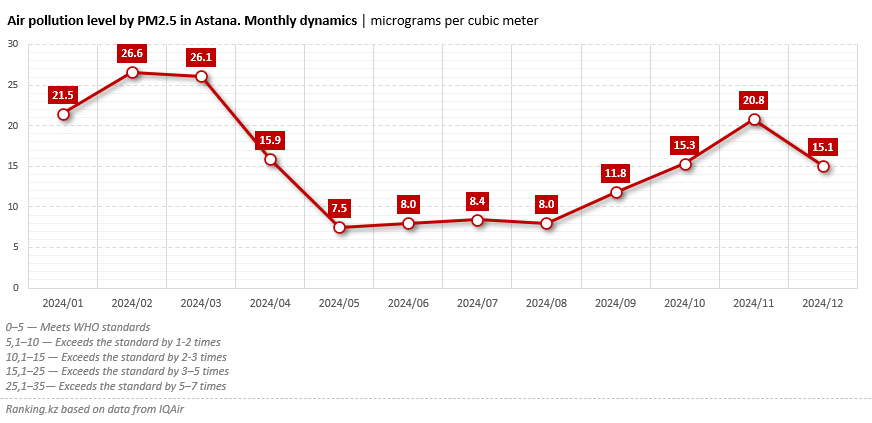

This trend is supported by international monitoring data. The Swiss company IQAir, which collects information on air pollution from fine particulate matter, published a report on the situation in Astana for 2024. The chart shows that the highest levels of air pollution in the capital occur in autumn and winter, reaching up to 26 micrograms per cubic meter, while in summer the level drops sharply — to 7.5 micrograms.

However, this is no cause for celebration. According to IQAir’s methodology, air is considered clean if particulate matter does not exceed 5 micrograms per cubic meter. In Astana, the summer level starts at 7.5 and reaches 8.4 micrograms, exceeding the standard by 1.5 times. In autumn, the exceedance is 2-3 times, and in winter, it reaches 3–5 times the acceptable limit.

Astana’s new environmental reality — “very polluted in winter, just polluted in summer” — suggests that stationary sources, which produce 138.7 thousand tonnes of emissions annually, are no longer the main contributors to the city’s air pollution. The leading factor is now transportation.

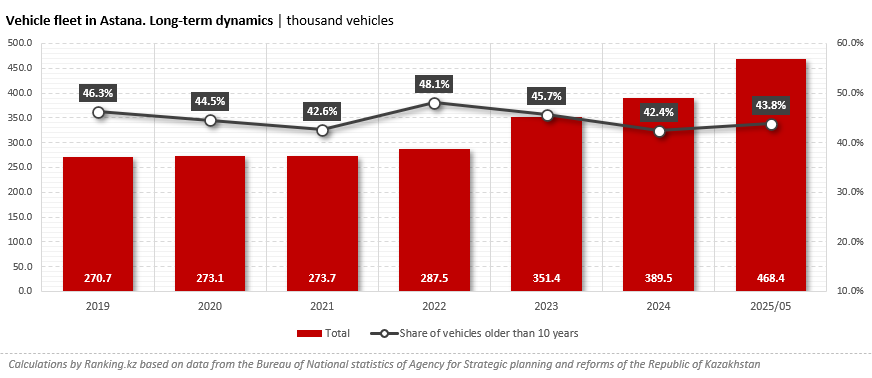

According to the Bureau of National Statistics of the Agency for Strategic Planning and Reforms of the Republic of Kazakhstan, as of early June, 468.4 thousand vehicles were registered in Astana. Compared to 2024, this represents a 20.3% increase, or 78.9 thousand additional vehicles. The most rapid annual growth in the vehicle fleet has been observed since 2022. This trend aligns with migration patterns into the capital, as internal migrants from other regions — many of them car owners — continue to relocate to the city.

One in five vehicles on Astana’s roads is equipped with outdated exhaust systems and effectively qualifies as scrap. Of the 468.4 thousand registered vehicles, more than 98.7 thousand are over 20 years old. The share of vehicles older than 10 years is also significant — 43.8%. This trend has remained unchanged in recent years, pointing to a sluggish renewal of the city’s vehicle fleet. Notably, more than 2.6 thousand buses over 20 years old are still in operation — accounting for 29% of the total bus fleet in the city.

The continued reliance of Astana’s public transport operators on outdated buses — rather than transitioning to modern models, ideally electric — is a direct responsibility of the city’s administration, which oversees urban transit. In recent years, the city has purchased 300 electric buses. Yet, according to available data, this is merely a drop in the ocean. As of early June, only 68 of Astana’s 9,000 buses were electric, with an additional 335 operating on hybrid fuel systems combining gasoline, gas-cylinder technology, and electricity. Combined, these account for just 4.5% of the city’s total bus fleet—an alarmingly low figure for one of the most environmentally polluted cities in the country.

Despite the worsening environmental conditions, the Astana akimat has yet to implement meaningful measures to address the issue. Notably, two years ago, the city’s Department of Environmental Protection and Nature Management proposed creating a low-emission zone that would ban high-emission gasoline and diesel vehicles from entering. However, the initiative was never put into action — lingering in the realm of "yes, but…"

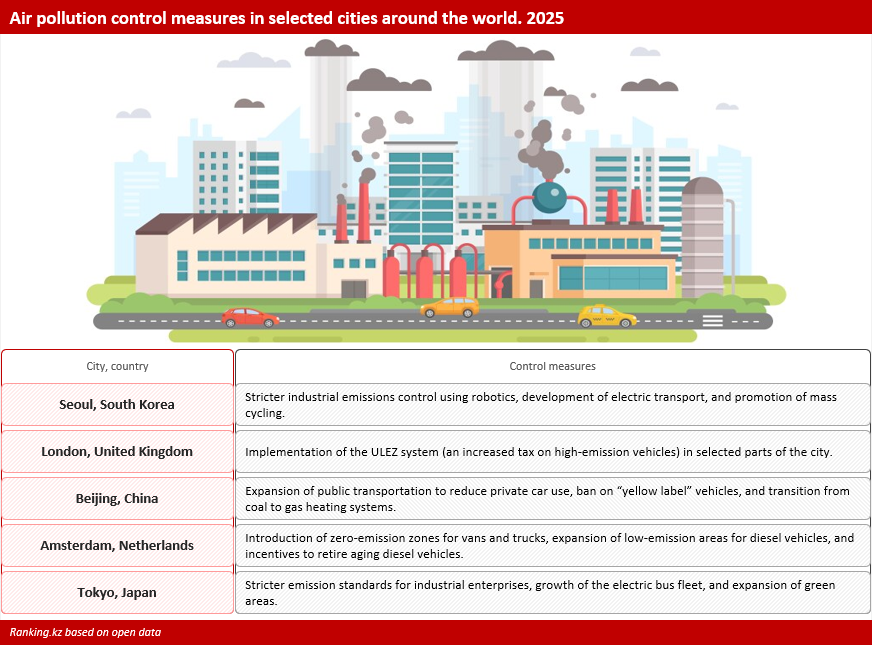

Such regulatory measures — applying pressure to reduce the share of aging vehicles — have proven effective in major cities around the world. London, for instance, introduced its Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) back in 2019, marking a major step in its efforts to combat air pollution. In designated neighborhoods, sensors now track vehicles entering the zone that fail to meet minimum standards: Euro 4 for gasoline cars and Euro 6 for diesel. These vehicles incur daily charges ranging from €12 to €100 — high enough to prompt many drivers to reconsider and switch to cleaner transportation.

What environmental policies could Astana officials adopt from international peers to help clear the city's air? Here are a few examples.

South Korea’s capital, Seoul, had long ranked among the cities with the highest air pollution levels globally. In response, city authorities launched an emissions reduction program. One of the first steps was deploying autonomous robotic systems and drones to monitor pollution in industrial zones. Seoul also launched transportation initiatives: phasing out or upgrading old vehicles, promoting electric transport and cycling, and tightening construction site inspections — often major sources of dust.

In Beijing, a five-year air quality improvement program is set to conclude this year. The plan aims to reduce the number of heavily polluted days in the Chinese capital to no more than 1% annually by the end of 2025. In 2024, for example, only two such days were recorded. Among the key measures implemented were transitioning from coal to gas heating systems and banning the use of so-called “yellow label” vehicles — those that fail to meet emissions standards.

In short, successful case studies abound. Unfortunately, progress in Kazakhstan remains modest by comparison.