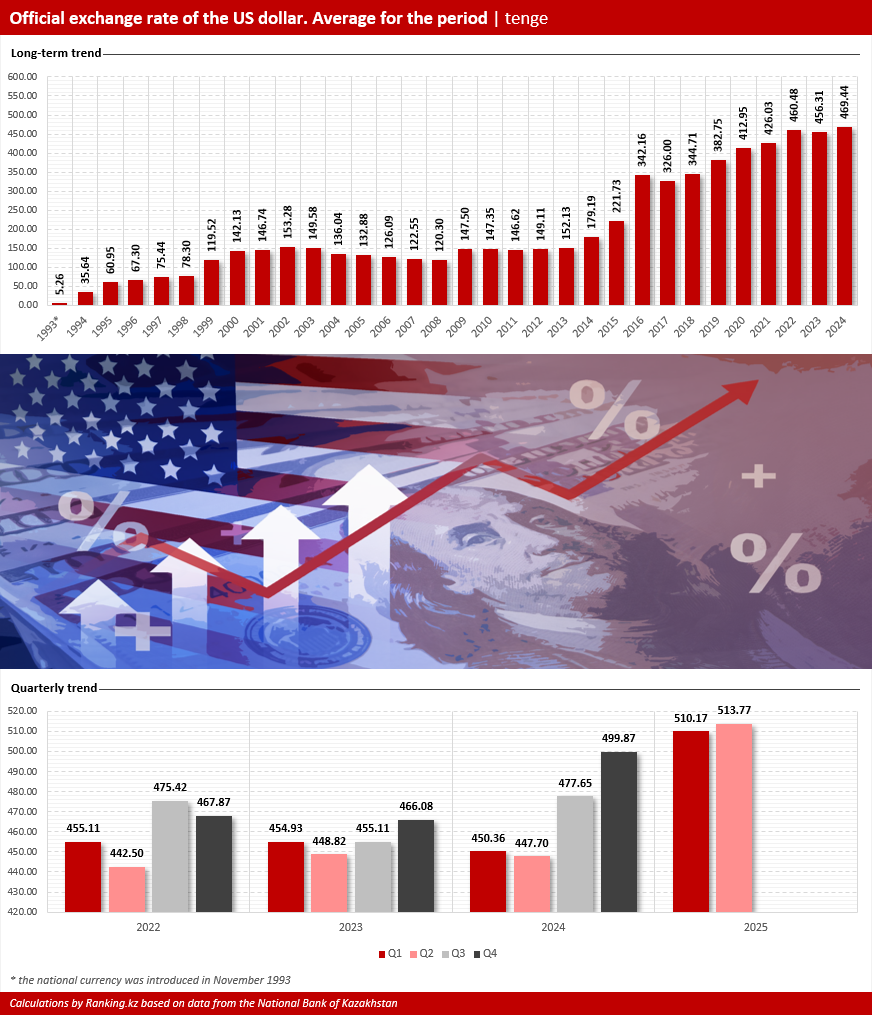

The US dollar has risen from 5.26 tenge at the time Kazakhstan’s national currency was introduced in 1993 to 536.8 tenge in September 2025. Over the past three decades, the pattern has remained the same: every new crisis has brought a depreciation of the tenge, while periods of relative stability proved short-lived.

In the 1990s, the dollar surged 27-fold. In the 2000s, the pace slowed, but the 2008 crisis once again sent the tenge tumbling. The last major turning point came in 2015–2016, when the dollar jumped from 221.7 to 342.2 tenge in just one year — a 23.7% increase. Since then, the trend has only intensified: by 2024, the average exchange rate reached 469.4 tenge per dollar.

Short-term data suggest that 2025 has marked an accelerated phase of the tenge’s decline. Between 2022 and 2024, the average quarterly rate hovered between 442.5 and 477.7 tenge per US dollar, weakening to nearly 500 in the fourth quarter of 2024. This year, however, the rate averaged 510.2 in the first quarter and 513.8 in the second.

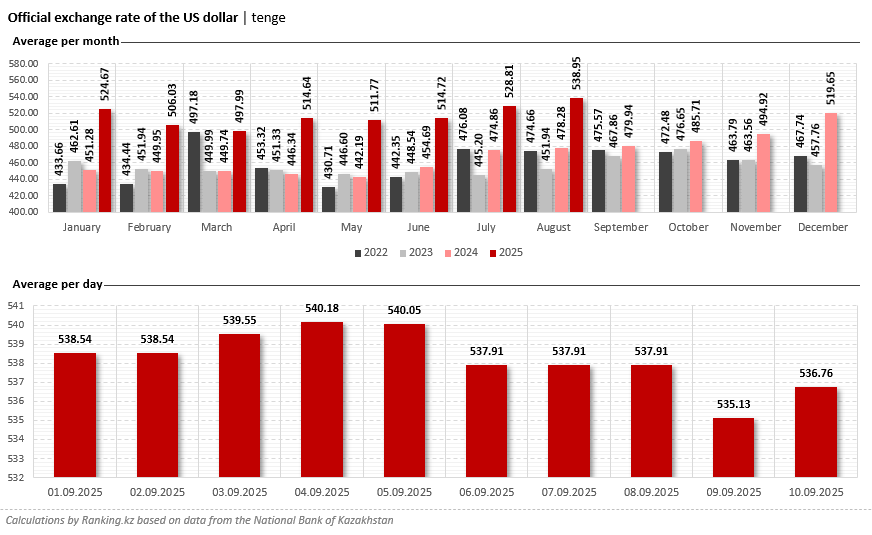

On a monthly basis, the trend is even more striking. In January 2025, the dollar stood at 524.7 tenge, rising to 528.8 in July and reaching 539 in August. In effect, the US dollar gained 2.7% in just eight months, and 12.7% compared to August of last year.

Official data from the National Bank of Kazakhstan for the first ten days of September 2025 show the dollar consistently trading above 535 tenge, peaking at 540.2. Even during periods of relative calm, the exchange rate has not fallen below this threshold. This suggests that the market now perceives the tenge’s weakness as the new normal rather than a temporary spike.

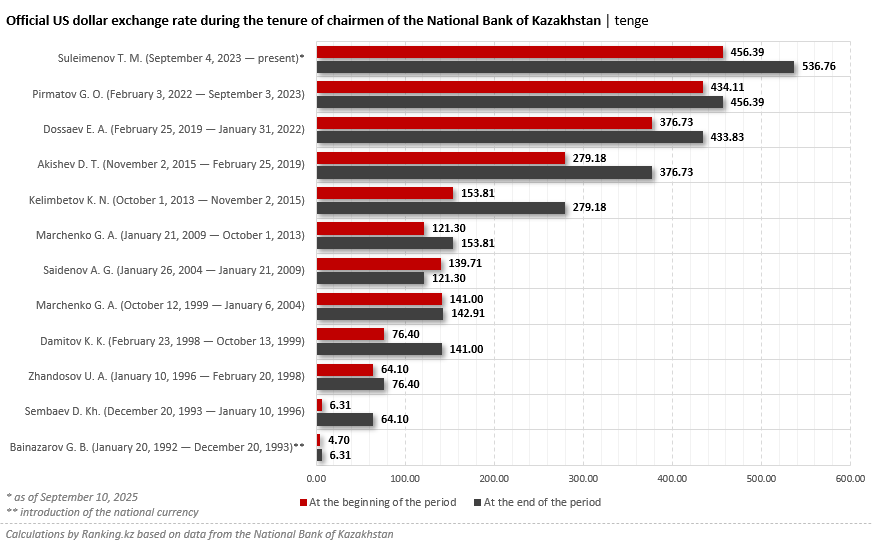

The history of leadership changes at the National Bank of Kazakhstan reveals a clear pattern: every new chairman has ended his tenure with a significantly weaker currency than at the time of appointment. In the 1990s, under the first three heads of the regulator—Sembaev, Zhandosov, and Damitov (excluding Bainazarov, who oversaw the introduction of the tenge in November 1993 but stepped down a month later) — the dollar rose from 6.3 to 141 tenge. This was the era of Kazakhstan’s early market economy, when the national currency was still taking shape and the regulator lacked effective stabilization tools.

In the 2000s, the picture shifted only partially. Grigory Marchenko, in his first term, kept the rate almost unchanged. Under Saidenov, the tenge even strengthened from 139.7 to 121.3 per US dollar between 2004 and 2009. But that appreciation was driven entirely by record oil prices and surging investment inflows, not by systematic regulatory policy. During Marchenko’s second chairmanship (2009–2013), the dollar gained another 30 tenge, reflecting the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

The steepest collapse came under Kelimbetov (2013–2015), remembered for presiding over one of the sharpest devaluations in Kazakhstan’s history, when the dollar jumped from 153.8 to 279.2 tenge in just two years. It was under his watch in 2015 that the National Bank announced the move to a “free float.” In practice, this meant a one-off devaluation and the government stepping back from fixing the rate directly, rather than a true strengthening of market mechanisms.

Akishev (2015–2019) cemented this new, higher level, with the dollar reaching 376.7. Dosaev (2019–2022) pushed it to 433.8, and Pirmatov (2022–2023) to 456.4. Today, under Timur Suleimenov, the dollar stands at 536.8 as of September 10, 2025, with the trend again appearing irreversible.

The conclusion is consistent: only during Saidenov’s tenure did the tenge strengthen, and that was solely thanks to a commodities boom. In all other cases, each new chairman left behind a weaker currency. This underscores that the regulator’s policy remains reactive: the tenge can strengthen only under conditions of record-high exports at favorable prices. Even the shift to a “free float” did not alter the broader trajectory. The exchange rate stabilizes only during external calm but plunges into a tailspin at the first sign of shock.

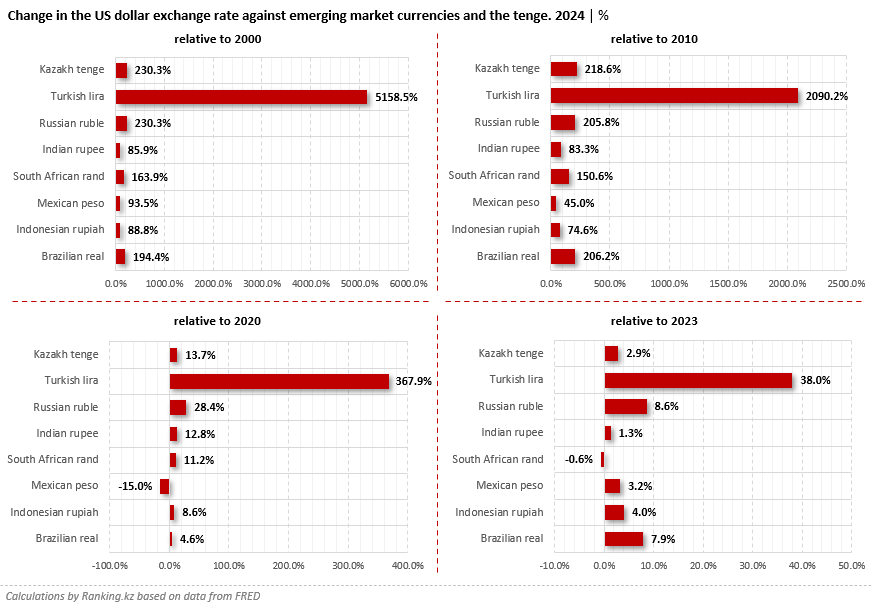

The National Bank of Kazakhstan often cites “global trends” and the weakness of emerging markets. Yet the numbers show that the tenge has depreciated much more sharply than most developing-world currencies. Over the long horizon from 2000 to 2024, the tenge weakened by a factor of 3.3 — exactly the same as the Russian ruble. By comparison, the Indonesian and Indian rupees lost less than 90% of their value, while the Mexican peso declined by 93.5%. The Turkish lira, which collapsed more than 52-fold over the same period, is generally seen as an outlier.

Since 2010, the pattern is similar: the tenge has depreciated 3.2 times against the US dollar, while the ruble and the Brazilian real weakened 3.1 times. In contrast, the Indian and Indonesian rupees fell by only 74.6%–83.3%, and the Mexican peso by just 45%.

On a shorter horizon, the contrast is even sharper. Between 2020 and 2024, the tenge lost 13.7%, the Indian rupee 12.8%, the Indonesian rupee 8.6%, and the South African rand 11.2%. The Mexican peso, however, strengthened by 15% against the dollar, standing out as an example of successful macroeconomic policy.

In 2023–2024, the tenge slipped 2.9%. For comparison, the Brazilian real and the Russian ruble lost more (7.9% and 8.6%, respectively), while the Indian rupee depreciated 1.3%, the Indonesian rupee 4%, and the Mexican peso 3.2%. Once again, the Turkish lira was the clear outlier, plunging 38%. The South African rand, meanwhile, strengthened 0.6% against the US dollar.

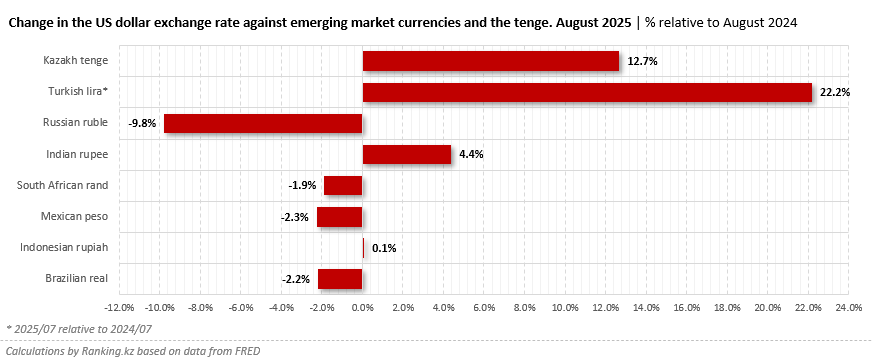

The latest data are particularly telling. By the end of August 2025, the US dollar had gained 12.7% against the tenge over the year. Over the same period, however, it weakened against the Brazilian real (down 2.2%) and the South African rand (down 1.9%). As of July, the dollar had surged 22.2% year-on-year against the Turkish lira, while edging up just 0.1% against the Indonesian rupiah. Against the Russian ruble, by contrast, the dollar fell sharply, losing 9.8%.

This places Kazakhstan consistently among the underperformers in the currency market, despite its commodity revenues and relatively modest public debt.